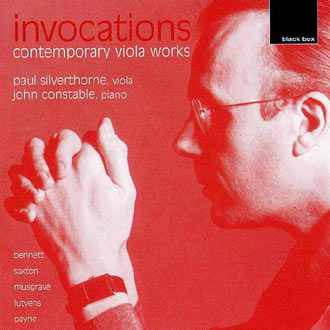

“Invocations” - Contemporary Viola Works

Paul Silverthorne - Viola

John Constable - Piano

Black Box BBM 1058

The Scotsman

"The viola is triumphant in this disc of new music featuring violist Paul Silverthorne and accompanist John Constable. It's all here, from the sharp, crystalline edges of Stuart MacRae's music and spicy cocktails of Jukka Tienssu's and Elisabeth Lutyens, to the sweet lyrical lines of Thea Musgrave, Richard Rodney Bennett and John Woolrich. "

Kenneth Walton

Musicweb July 2001

“With this disc Paul Silverthorne triumphantly reinforces his position as commissioner and executant of contemporary viola music. With the exception of Lutyens all the composers here are still vigorously active - and Lutyens' influence is reflected in her two pupils, Saxton and Hawkins; most of the composers are British.

The longest piece is the first, Richard Rodney Bennett's After Ariadne. It demonstrates many of the qualities both Silverthorne and the viola encourage - allusion, reflection, and things veiled, hidden and emergent. Though not obviously in variation form Bennett unfolds his source - Monteverdi's madrigal Lasciate mi morire - only at the end of his lament. Clearly a model here must be Britten's Lachrymae. Both pieces share a sense of revelation and unfolding, a final simplicity of utterance reached through struggle - and if Bennett is not Britten's equal then at least his vision shares something of the older composer's transcendence.

Saxton's piece shares qualities of depth of tone, a certain keening - in his case specifically Jewish - and its fulfilment in a Rabbinic prayer, alluded to earlier but emerging at the close as a kind of benediction. The viola is well suited - tonally and expressively - to this kind of confidentiality of utterance; throughout the disc composers respond to darker tone colours and an element of fragility to produce works of searching depth. Thea Musgrave, for example, speaks of her little piece's “peaceful contemplation” but this belies its amplitude of expression, with a remarkable concentration of feeling and thought in its four minutes. Anthony Payne's Amid the Winds of Evening encompasses varying tempo and rhythmic features and shares with other pieces on this disc the great gift of saying much in a short span of time. John Woolrich, like Saxton and Bennett, turns to source material and like Bennett he has turned to Monteverdi. O sia tranquillo is especially hypnotic in its beauty. Colin Matthews' Oscuro is veiled, rocking, fractious and lyrical and impresses with its compelling aloofness.

But all the works impress; from Lutyens' own piece, the most fearsomely difficult with its agonizing quadrupal stopping, through Hawkins' dark explorations of colour and feeling, MacRae's fascinating sonorities and finally Kampela and Tiensuu; the former aggressive and the latter exploring the journey from taut rhythmic attack to benevolent silence.

From extreme technical demands to lyric simplicity, from tonal amplitude to wisps of sound, Silverthorne and John Constable, the most responsive pianist, emerge as worthy ambassadors of the contemporary literature in a disc of which Black Box should take great pride.”

Jonathan Woolf

The Times, May 22nd 2001

"...Paul Silverthorne is a no less fruitful source of new music. Eleven new pieces on his album Invocations (BBM1058) reveal just a cross-section of his work. Colin Matthews offers his darkly oscillating Oscuro for piano and viola; Anthony Payne is represented by a solo called Amid the Winds of Evening whose 'twilit unease' explores extremes of pitch and timbre as a sharp animal fear and a sense of the numinous meet in veiled human angst. Elisabeth Lutyens' Echo of the Wind is a virtuoso soundscape of juddering tremolandi and harmonics. It's followed by a compelling piece by her protégé Robert Saxton. Invocation, Dance and Meditation is a witty and rhapsodic tribute to the shifting patterns of Hassidic prayer, and it's performed with Silverthorne and John Constable's characteristically eloquent bravura. "

Hilary Finch

Amazon.co.uk Review

"On Invocations, master violist Paul Silverthorne brings together a valuable collection of pieces he has commissioned from today's composers and plays them all with warmth and expression, while pianist John Constable partners him with constant skill and sensitivity (some of the items are unaccompanied). In all, 11 mainly British composers are represented, ranging from distinguished senior figures such as Thea Musgrave, Robert Saxton and Richard Rodney Bennett to the younger and less well-known Scot Stuart MacRae, the Brazilian Arthur Kampela and the Finn Jukka Tiensuu. The latter provides the most challenging piece here with Oddjob--a five-minute work that creates fascinating textures by shadowing a live viola with its electronically recorded equivalent. Of the more traditional works, particularly striking is Saxton's finely imagined Invocation, Dance and Meditation, whose origins lie in ancient Jewish religious and musical traditions. Equally rewarding are the lyricism of the biggest piece, Bennett's After Ariadne, based on Monteverdi's madrigal Lasciatemi morire, and Colin Matthews'--to use his own word--“cryptic” Oscuro. But everything is worth hearing and much of this music should appeal far beyond the boundaries of viola specialists or new-music addicts. "

George Hall

The Strad - September 2001

"This CD offers a selection of pieces written for Paul Silverthorne, principal viola of the London Symphony Orchestra and the London Sinfonietta and an indefatigable promoter of the viola and its repertoire. The best possible case is made for each piece, which is introduced in the booklet in the composer's own words and commented on by their dedicatee. I have heard many of these pieces within the context of a mixed Silverthorne recital, which is surely the way to do it: listening to this CD in one go is definitely to be avoided! In small doses, though, the recording proves uniquely fascinating, offering a conspectus of mostly British composing styles from the past 15 years or so.

Richard Rodney Bennett's After Ariadne uses Monteverdi's theme (which Britten-like, appears in its original form at the end) as the basis for its lyrical ruminations. Robert Saxton's Invocation, Dance and Meditation is based on traditional Jewish religious chants (but manages not to sound like Bloch). Hawkins' powerful Urizen (after William Blake's poem) was the first of the many pieces written for Silverthorne and has managed to establish a toe-hold in the repertoire. I would like to draw the listeners' attention to Arthur Kampela's riot of sound and noises and Jukka Tiensuu's electronically generated welter of sounds: these two unaccompanied pieces were written (and learnt!) in a matter of days when an orchestra proved unable to learn the scheduled concerto by B.A. Zimmerman.

Together with his long-standing piano partner, Silverthorne proves an ideal advocate of each composer's style, even when in Kampela's piece he has to draw from his Amati sounds that were undreamt of in its maker's philosophy."

Carlos Maria Solare

BBC Music Magazine - September 2001

"Even though the cause of the viola needs no special pleading these days, it helps to have players like Paul Silverthorne around. Principal viola of both the London Symphony Orchestra and London Sinfonietta, he has coaxed, cajoled and inspired composers mightily to extend the contemporary repertoire. Sometimes, as in the case of Elisabeth Lutyens and her Echo of the Wind, the response has been aggressive, testing player and instrument (a rich-toned Amati on loan from the Royal Academy of Music) to their limit. Other examples, such as Robert Saxton's tribute to the Hassidic tradition, Invocation, Dance and Meditation, have been fruitful studies in collaboration between player and composer, or, in the case of John Hawkins's Blake-inspired Urizen, keen-eared responses to the instrument's potential for dark utterance through soulfully eloquent melody. Interestingly, memory proves central to several other works in this gallery. Both Richard Rodney Bennett's After Ariadne and John Woolrich's Three Pieces invoke the music of Monteverdi. Oscuro, by Colin Matthews, looks to its own past in an earlier essay, Chiaroscuro, also written for Silverthorne. Thea Musgrave, Anthony Payne and Stuart MacRae each offer a thoughtful and characteristic miniature, while works by Brazil's Arthur Kampela and Finland's Jukka Tiensuu offer more avant-garde perspectives.

Performance: ***** Sound: ****”

Nicholas Williams

The Musician - September 2001

"The very enterprising CD label Black Box has released a new CD by one of our top viola players, Paul Silverthorne, principal viola of the London Symphony Orchestra and the London Sinfonietta.

What is on offer is a wide-ranging mixture of contemporary music by 11 different composers that is very comprehensible and enjoyable. Unfortunately, there is not space to describe them all but Richard Rodney Bennett's After Ariadne, based on Monteverdi's madrigal Lasciate mi Morire is wonderfully composed for both instruments. John Hawkins' Urizen is a haunting work composed with real passion and lyrical conviction. Colin Matthews' intriguing twilight work Oscuro travels through landscapes of semi-dream and awareness before coming to a quiet conclusion. The City Inside by Stuart MacRae is dramatic and very positive right from the very first bars. This invigorating work alternates between bristling hard-edged energy and softer moments of less tension.

Paul Silverthorne's engaging and full toned playing is excellent throughout, as is his understanding of all the composer's different musical styles. The ever reliable pianist John Constable provides all the musical reassurance that a soloist could wish for. An excellent CD. "

Graham Williams

Classical London

"Paul Silverthorne is a 'real' violist; his sound is distinguished and couldn't be confused with a thin cello or veiled violin. The recording is consistently excellent despite three locations, and the booklet notes are informative.

That the viola doesn't have the profile of the violin and cello is perhaps explained by it being a 'middle voice' and thereby restricted... It doesn't lack for repertoire - Berlioz's Harold in Italy, Brahms's two sonatas, and concertos by Bartók, Hindemith (himself a violist) and Walton come easily to mind - yet there's the notion that the viola is not capable of brilliance and fleet-fingered virtuosity. It can certainly speak in anger and is capable of rapid-fire delivery - as the music on this enterprising CD demonstrates.

Richard Rodney Bennett's impressive After Ariadne is a dramatic scena. Its Brittenesque journey culminates in a full statement of a madrigal by Monteverdi, who also features in John Woolrich's Three Pieces, affecting off-cuts from his Viola Concerto. Robert Saxton's Invocation, Dance and Meditation is inspired by “ancient Jewish religious and musical traditions” - an increasingly ecstatic ascent is followed by sonorous reflection. Stuart MacRae is a composer to follow, as his Proms 2001 Violin Concerto showed. His tense 8-minute drama, The City Inside, had a storm as its starting-point, the viola aggressive and acerbic. Similarly, Elisabeth Lutyens exploits nature, and technical facility, in Echo of the Wind; this and Anthony Payne's discursive Amid the Winds of Evening are the finest of the unaccompanied pieces.

The viola's capacity for nocturnal musings is the core of Thea Musgrave's In the Still of the Night and Colin Matthews's shadowy Oscuro. Each listener will have different favourites. "

Colin Anderson

Gramophone

"Familiar as lead viola in the London Symphony Orchestra and London Sinfonietta, Paul Silverthorne here demonstrates his credentials in contemporary recital fare, all of which he commissioned. Bennett's extended scena continues the vein of nostalgia-tinged lyricism evident in his recent music, though the scherzando sections recall the rhythmic agility long central to his expression, and most likely indicate the Monteverdi madrigal that provided inspiration. Musgrave's contemplation features modal-sounding harmonies, while Lutyens' typically pungent miniature runs the gamut of viola technique in pursuit of the instrument's soul. Two of her protégés are represented: Saxton draws on ancient Jewish prayer, the piece given an evocative context through its tonal centering on E; while Hawkins offers a more discursive though hardly less potent depiction of Blakeian fall from grace.

Pieces drawn from a 1988 anthology demonstrate three strikingly divergent approaches to the viola. Payne's is an agitated study in tremolandi and fragmentation; Matthews revisits his contribution in a muted, expressive study in sombre shading; while Woolrich absorbs models in an inward-looking trilogy, concluding in a Monteverdian allusion of plaintive expectation. Whether or not MacRae's study in accumulating, maintaining and dispersing rhythmic velocity is an actual representation of his booklet-note description, it denotes a forceful musical persona.

Two 'last-minute' pieces round off the recital: Kampela's a hard-hitting interaction of pitched material with virtual white noise; Tiensuu employing tape delay in a riot of rhythmic superimposition and eventual diffusion of harmonics.

John Constable is his dependable self in five of the pieces, while the recording brings out the character of Silverthorne's Amati impressively. Booklet-notes, interspersing notes from the composers with background from the performer are a model of presentation. CD-Rom- compatible players can access four additional tracks, including an arrangement of Cole Porter's Ev'ry time we say goodbye; its wistful melancholy ideally suited to the viola's timbre. "

Richard Whitehouse

Classical Net Review 2007

"Paul Silverthorne has in a way run against the grain of the kind of violist you normally hear. He can play subtle, but he can also play with fire and call upon a “star-quality” tone that demands a listener's attention. Nevertheless, he doesn't indulge a “one-size-fits-all” approach. His color and approach change suitable to the music he performs. His Brahms sounds little like his Shostakovich. Furthermore, he has done his bit to increase viola repertoire by commissioning composers. Not only that, but composers apparently enjoy writing for him. Early on, he found himself in Elisabeth Lutyens's orbit. Lutyens, an important British composer whose music so far has remained shadowy outside of Britain, taught some of the best of their generation.

This CD gathers together Lutyens and her circle, as well as others. The music takes a little effort, but it also rewards the effort. You won't find an out-and-out dud in the entire program, and you will encounter at least two stunners. Furthermore, you place yourself in the hands of two master interpreters - Silverthorne and pianist John Constable - who've played together for years.

The program opens with one of its strongest pieces, Richard Rodney Bennett's After Ariadne. Bennett made his first splash in the Fifties, notable both for his jazz-based pieces and for his forays into dodecaphony.

He has also enjoyed some success in commercial fields, notably his film music, particularly his much-admired score for Murder on the Orient Express. He has also accepted such assignments as orchestrating Paul McCartney's Standing Stone. One's impressions of a composer obviously arise from the pieces one has heard. The spottier the acquaintance, the less reliable the judgment. I had thought of Bennett as technically brilliant, facile, but ultimately uninvolving. After Ariadne turned me around. This major work, a single movement lasting almost a quarter hour, grows out of its opening notes - pretty much monothematic, in fact.

To some extent it's a fantasia, but one with great structural cohesion as well as a solid dramatic plan. Bennett has shaped something original, sui generis, and substantial. It yearns, it sings with great tenderness and a noble, slightly restrained passion. Toward the end, the theme begins to break free of its dissonant setting and resolve into Lasciate mi morire (also known as Lamento d' Arianna) from Monteverdi's sixth book of madrigals, thus illuminating the title. We get a straightforward quote from the madrigal, before the mists rise again and surround the theme.

At this point, the Scottish composer Thea Musgrave has made her reputation on her operas. She may be as familiar in the U.S. as in Britain, probably due to her long residency here. The title In the Still of the Night of course conjures up the Cole Porter song, but Musgrave doesn't have this in mind. Instead, she writes a nocturne for viola alone. The work has a weight all out of proportion to its length. It proceeds with the stateliness of a Bach sarabande.

Elisabeth Lutyens, daughter of the great British architect, has immense importance as both a teacher and as an historical figure in British music. One of the earliest British serialists, her music shows a rare, practically Webernian refinement. Indeed, that may lie at the root of her lack of acceptance even among new-music people. Recordings of her music show up once in a blue moon. I treasured an LP of her O saisons, o chateaux” bankrolled by the Gulbenkian Foundation. Major scores go unperformed and unrecorded. Echo of the Wind for solo viola is another night piece. It is the devil to play, exploiting rapid passages of high harmonics and changing colors practically with every measure. Note that we don't get the wind itself, but its echo, wisps of wind as it were. It seems written serially (I can't be sure without a score), but that misses the larger rhetorical and architectural point, a three-part structure laid out as a dynamic arch.

Robert Saxton's Invocation, Dance, and Meditation is yet another arch. It begins as a kind of cross between Bloch and Britten (of the Holy Sonnets of John Donne), with a slow, quiet opening. Eventually, both the tempo and dynamic increase, and the rhythms become more agitated until we find ourselves in the middle of a dance. Things then slow down and quiet down to the end. Saxton admits to the inspiration of Hassidic prayer. Of all the works here, it runs to the more conservative side of things, particularly surprising from a student of Lutyens and Berio, but it's still a solid piece.

Currently one of my favorite British composers, John Hawkins, a student of Lutyens and Malcolm Williamson, has built an impressive body of work and a solid reputation among British musicians. Recording companies have yet to discover him, but I believe they will. A roster of distinguished performers champion his work. Again, he comes from the conservative wing. The shade of Hindemith lurks behind Urizen, but that indicates merely a starting point. Hawkins speaks his own poetry. Urizen, of course, is William Blake's demon of eighteenth-century rationality, usually the villain of his longer poems. I confess I don't see much relation between Blake and the music, even when Hawkins goes so far as to quote a passage in his remarks, but fortunately the piece's success doesn't depend on a program. This piece combines structural rigor - two or possibly three ideas constantly put into new relationships with one another - with a darkly dramatic sensibility. Hawkins has also written pieces under the inspiration of the sea, and this piece strikes me as coming from the North Atlantic. It begins with a lengthy intro for solo viola, in which the composer lays out his basic ideas. Most solo-instrument passages bore me to death, but this grabs my attention and shuttles me along. The piano enters, and we get an almost-bluesy passage as the piece works itself into a neurotic, passionate waltz before it dies down toward the end.

Colin Matthews, a student of Nicholas Maw, hung around Britten and Imogen Holst in a kind of apprenticeship. Due to his “completion” of Gustav Holst's Planets with a “Pluto” movement, he's probably the best-known composer on the program. I don't particularly care for his work in general, and Oscuro doesn't prove an exception. It sticks to the viola's middle and lower range and supports it with an even lower piano. It never goes anywhere with any real point. A gray piece stuck in bland.

His brilliant “elaboration” of Elgar's Third Symphony from the composer's scraps and late incidental music showed at the least that Anthony Payne knew his Elgar. It prompted me at the time to seek out Payne's original music. The enterprising British label NMC has recorded a number of his works. Silverthorne may put Among the Winds of Evening so close to the Lutyens. Compared to Echo of the Wind, the Payne, also for solo viola, appears a bit raw. However, it also works more directly on a listener's feelings. It begins in a “painterly” way, depicting not gentle evening breezes, but gusts, and builds to passionate cries.

The wind and sea also inspire John Woolrich's 3 Pieces for Viola. Or, rather, three musical evocations do: Soave il vento from Cosi fan tutte, Torna il tranquillo al mare from Monteverdi's Il Ritorno d'Ulisse in Patria, and Monteverdi's madrigal O sia tranquillo il mare from Book VIII. It pursues the same strategy as Bennett's After Ariadne, but on a much smaller scale - epigrams, rather than meditations.

Saxton's pupil Stuart MacRae wrote his The City Inside out of a childhood memory of a thunderstorm at night. Once again, the painterly yields to the dramatic, as the depiction of pelting rain moves into inner storms of Bernsteinian cross-rhythms.

The program winds up with scores by Arthur Kampela, a Brazilian living in New York, and the Finn Jukka Tiensuu. Both composers probably write the most “advanced” music here, and both contribute strikingly similar pieces. Both explore a new kind of polyphony, within the framework of a solo viola, and both try to trick the ear into believing it listens to more than one instrument. Kampela's Bridges does this by distinguishing “tone” and “noise” and by exploiting simultaneously the two extremes of the viola's range. Tiensuu's Oddjob creates the illusion of two instruments through electronic echo and delay as well as by sharp stereo separation. Both pieces are brilliant and bravura fun, in a way similar to Liszt's Hungarian rhapsodies, without partaking of that idiom.

Silverthorne sails through all of this. The virtuoso technique one tends to take for granted. However, his ability to make living music over a gamut of contemporary styles really impresses. He's not just playing notes. He shapes each piece and gives each one a strong forward impulse. It's almost as if he's in each composer's head. And Constable is his equal. Beautifully recorded, besides."

Steve Schwartz